Comparing Design RatiosJay E. Paris | December 13, 2015

Given the infinite number of variables involved, making any kind of objective comparison between two different sailboat designs might, at first, seem impossible. However, with the help of design ratios, you can not only compare and contrast different designs, but get a pretty good idea, sight unseen, as to how a boat is going to perform under sail.

The first of these, the Displacement-Length Ratio (D/L) is a nondimensional expression of how heavy a boat is relative to its waterline length. A D/L ratio is calculated by dividing a boat’s displacement in long tons (2,240 pounds) by one one-hundredth of the waterline length (in feet) cubed. Because the displacement in long tons can be expressed as a volume (cubic feet of seawater), and since length-cubed is also volumetric, the result of the D/L formula is nondimensional, i.e., it is no longer tied to a particular physical size. This means the D/L can be used to compare the relative “heaviness” of boats no matter their size. For example, a boat with a 25-foot waterline and one with a 50-foot waterline are equally heavy relative to their respective waterline lengths if they have the same D/L ratio. The relative heaviness of boats is often categorized as follows: These gradations are applicable to current designs, which tend more toward reduced overhangs and longer waterlines than earlier boats. Most sailboat designs of the 1930s through the 1960s had D/Ls (as they are often referred to) above 300, but with their long overhangs their sailing length was increased as they heeled, resulting in “effective” D/Ls at speeds that were well below their calculated values. The significance of the displacement-length ratio is that the lighter a boat is relative to its waterline length, the higher its speed potential, especially when in displacement mode. If there is less water to push aside, wavemaking drag is reduced. Some ultralight-displacement boats, or ULDBs, are light enough to plane just like a powerboat, in which case a low D/L gives some indication how quickly and easily a design will transition out of displacement mode. (Although hull shape is also important.)

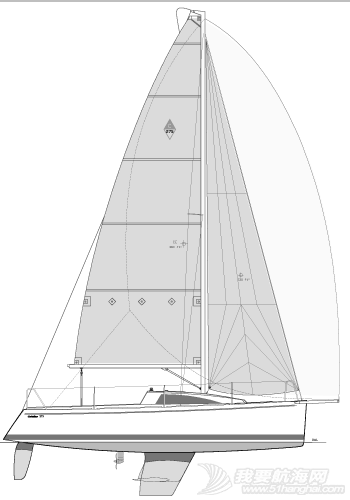

While at first it might seem desirable to always have as low a D/L as possible, as in most aspects of yacht design there are trade-offs. In general, the lower the D/L, the less comfortable the boat’s motion will be in a seaway and the more sensitive the boat is to overloading. Another important design parameter is the Sail Area-Displacement Ratio (SA/D), another nondimensional calculation that expresses the relationship between a boat’s sail area and its displacement. Traditionally, it is calculated by dividing the nominal sail area in square feet by the boat’s displacement in cubic feet to the two-thirds power. In this case, displacement is converted from pounds to cubic feet by dividing it by 64, the weight of a cubic foot of seawater. The standard displacement used by most designers for comparative purposes is the half-load displacement, calculated with the boat equipped for sailing with the crew and half the consumables (provisions, water, fuel, supplies) on board. The nominal sail area is calculated as the sum of the foretriangle area (one-half the base, or J dimension, multiplied by the height, or I dimension) and the mainsail area (one-half the foot, or E dimension, multiplied by the hoist, or P dimension). It’s important to note, however, that naval architects (and marine journalists) are increasingly using actual sail areas for mainsails, in particular, because the nominal area fails to account for the larger roaches often flown on modern rigs.

The SA/D is also nondimensional because sail area in square feet is divided by a displacement term that has been converted from cubic to square feet. This mathematical manipulation results in a parameter that again is independent of boat size. Therefore, a 30-footer with a SA/D of 20 will have just as powerful a rig as a 60-footer with the same SA/D.

The SA/D is also nondimensional because sail area in square feet is divided by a displacement term that has been converted from cubic to square feet. This mathematical manipulation results in a parameter that again is independent of boat size. Therefore, a 30-footer with a SA/D of 20 will have just as powerful a rig as a 60-footer with the same SA/D. In general terms, a boat having a sail area-displacement ratio under 15 would be considered undercanvased; values above 15 would indicate reasonably good performance; and anything above 18 to 20 suggests relatively high performance, provided the boat has sufficient stability and a low enough displacement-length ratio to take advantage of its abundant sail area. The SA/D is analogous to an automobile’s horsepower-to-weight ratio, with sail area being a measure of power, and displacement being indicative of wavemaking drag. The principal components of drag are friction and wavemaking; since wavemaking increases disproportionally with speed, the SA/D is indicative of performance in moderate- to heavy-air conditions. It is important when comparing the SA/Ds for different boats to be certain that the sail area and displacement values are measured in the same way for each boat. In SAIL’s New Sailboat Review, we typically calculate ratios using the mainsail and 100% foretriangle area. On occassion a boatbuilder may publish sail areas and displacements that are larger and lower than nominal so as to maximize a boat’s SA/D ratio in the interest of making appear to be higher performance. This is done by quoting the area of an overlapping genoa, or in the case of displacement, publishing the light-ship weight of the boat as shipped from the builder rather than the half-load displacement. Finally, there is the Ballast Ratio, or the amount of ballast a design is carrying. Unlike the first two ratio, this one requires no fancy conversions of units: simply divide the weight of the ballast by the half-load displacement, and then multiply by 100. The higher the number, the greater the righting moment, i.e. the greater to ability to resist heeling.

Typically, a ballast ratio of 40 or more translates into a stiffer, more powerful boat that will be better able to stand up to the wind. However, it’s imporant to be aware that ballast placement also plays an important role in righting moment: for example, the same weight of internal ballast will provide far less righting moment than at the very tip of a deep fin keel. Therefore, ballast ratios are somewhat less determinent than the first two. While righting moment if obviously important to good sailing performance, this is another area in which is it possible to have too much of a good thing. Specifically, a boat with an aggresive righting moment will have a faster, more aggresive motion in a seaway, which can be hard on crews. If you’re only spending an afternoon racing around the buoys, then comfort may not be especially important. However, “seakindliness” as it’s called, can make all the difference in the world on a long passage.

|